Run out of town

The New York City Marathon was an annual celebration for Michael Capiraso for a decade. Five years post-cancelation, it remains a flashback-laden opener to the worst month of his year.

For the first time in six years, Michael Capiraso’s calendar was not blacked out the week leading up to the New York City Marathon. He had phone calls with ex-board members, coffee with “streakers” (people who have run 15 or more consecutive NYC marathons), an investor networking event, and dinner with a retired pro runner with a shelf of titles won on the streets of Manhattan.

If all you saw was his schedule, or heard from a friend “I saw Michael out at some place with some person,” you might think that he was back on track, right in the mix of things.

But there’s a reason why they call it cancelation, and not postponement.

Michael half-jokes that his schedule for the week before the marathon was a bout of exposure therapy. Exposure therapy is one of the many techniques his mental health practitioners deployed for his treatment-resistant depression and post-traumatic stress disorder over the last five years.

Those sessions were often structured around landmarks of New York City’s running scene—Michael’s personal and professional community for decades.

Going back amongst the community from which he was banished, he’s looking for a few breaks to go his away.

Heading into a call with a potential corporate partner, for example, Michael is in the unusual position of hoping the person on the other side didn’t do his homework. “I instantly think these people are googling me, and they’re going into this call thinking I’m the racist and sexist. That’s what’s happening. That’s what my life is. That’s the reality of it. That’s what I face with everything,” he says.

He has less to worry about now on this front than he has at any point over the five years since his cancelation. The top search results for his name are now articles that vindicate him and his record as CEO of New York Road Runners (NYRR); and that touch on the ongoing professional, social, and psychological consequences of his cancelation. There’s also an open letter signed by hundreds of runners from around the world calling on NYRR to apologize for their treatment of him in 2020, and their role in his cancelation.

But cancelation is a forward-facing trauma because the hoped-for remedy has painful side effects. Even positive press—this article included—leads the reader to ask: vindicated... from what? What was he accused of, tarred as, and fired over?

Cancelation: Behind the headlines

If you haven’t seen the headlines about Michael, you’ve seen plenty like them: a name, a title, and unquestionable epithets. Racist sexist. Toxic bullying environment. Inappropriate relationship, power imbalance.

These are the media humiliation and misrepresentation (MHM) component of cancelation. They have the same effect on the reader five years on as they did on day one: they brand the target as socially and professionally malignant.

Under any circumstances, they separate the target from their every social and professional community.

But during a moral panic—or three moral panics, as was the case in the summer of 2020—these articles are banishment decrees and banning orders. Anyone who gives the target a fair hearing or offers them a fresh start is aiding and abetting their social crimes—a good way to get yourself canceled.

From June to the week of Thanksgiving 2020, Michael was managing an institutional crisis. A group of former and current employees alleged that NYRR was insufficiently inclusive for marginalized communities, that NYRR was becoming a social club for affluent runners, and that NYRR’s leadership reflected that elite rather than the diversity of the five boroughs they were supposed to serve and represent. They aired their grievances first internally, and then publicly via an anonymous Instagram account and a change.org petition, which included a call for Michael’s ouster.

Michael took these to heart, even as they became increasingly frivolous—“It’s like they were complaining about their Thanksgiving dinner,” a former NYRR executive said—and even though few called him out by name. One that did said that Michael, as CEO, had too close a relationship with the board chair, George Hirsch.

But Michael knew his record as CEO, and what the organization had accomplished during his five years at the helm. Most people at NYRR knew it, too. He had all the proof he needed to rebut the accusations both internally and, as necessary, in the media and amongst the global running community that looked to NYRR as the industry standard.

“Don’t worry, you can put all that away,” he was told by top board members. “We can handle this. You’re taking one for the team, so we’ve got your back.”

Michael thought he had a close personal, and still professionally appropriate, relationship with Hirsch. Michael had no reason to be wary when Hirsch asked him to come to his apartment the Monday before Thanksgiving, via a text that concluded with “big hugs” to Michael’s wife and daughters. At his apartment, Hirsch told Michael that he was being let go, The New York Times had the story, and Michael would have less than 24 hours to provide a statement to the Times.

The articles that The New York Times and Runner’s World published the Monday after Thanksgiving transferred all the accusations and innuendo directly and specifically onto Michael. NYRR could have rebutted the employees’ grievances using the facts and data Michael had had at the ready since June. Instead, the board cleared themselves of wrongdoing by pinning everything on him, and cleansed the organization of his transgressions by publicly firing and disowning him.

The board and the media changed the nature of the accusations—and the accusations themselves—by putting them entirely onto one person, and then putting that person’s name and face on the banishment order that went out worldwide. Those “high authority” sources spawned hundreds of articles, each one adding to the size, volume, and frenzy of the mob.

Michael’s psychiatrist (who was not the exposure therapist provider) identified three traumatic elements in his cancelation: shame, rejection, and betrayal.

Shame and rejection are standard aspects of cancelation and MHM. Betrayal is not.

“The betrayal stunned him,” this psychiatrist said. “He felt that these were people with whom he had worked, had a good relationship, and held themselves as ready to have his back and protect him.”

Betrayal is always a profound and destabilizing experience. But Michael’s betrayal by members of NYRR’s board, particularly a long-time friend and colleague, was even worse than that: it was the necessary, final ingredient for a cancelation that, years later, still had him asking “Do I want to keep living?”

Exiled in your own backyard

Not long after he answered “Yes” for the final time, three years post-cancelation, I glimpsed the extent of Michael’s avoidance behaviors firsthand.

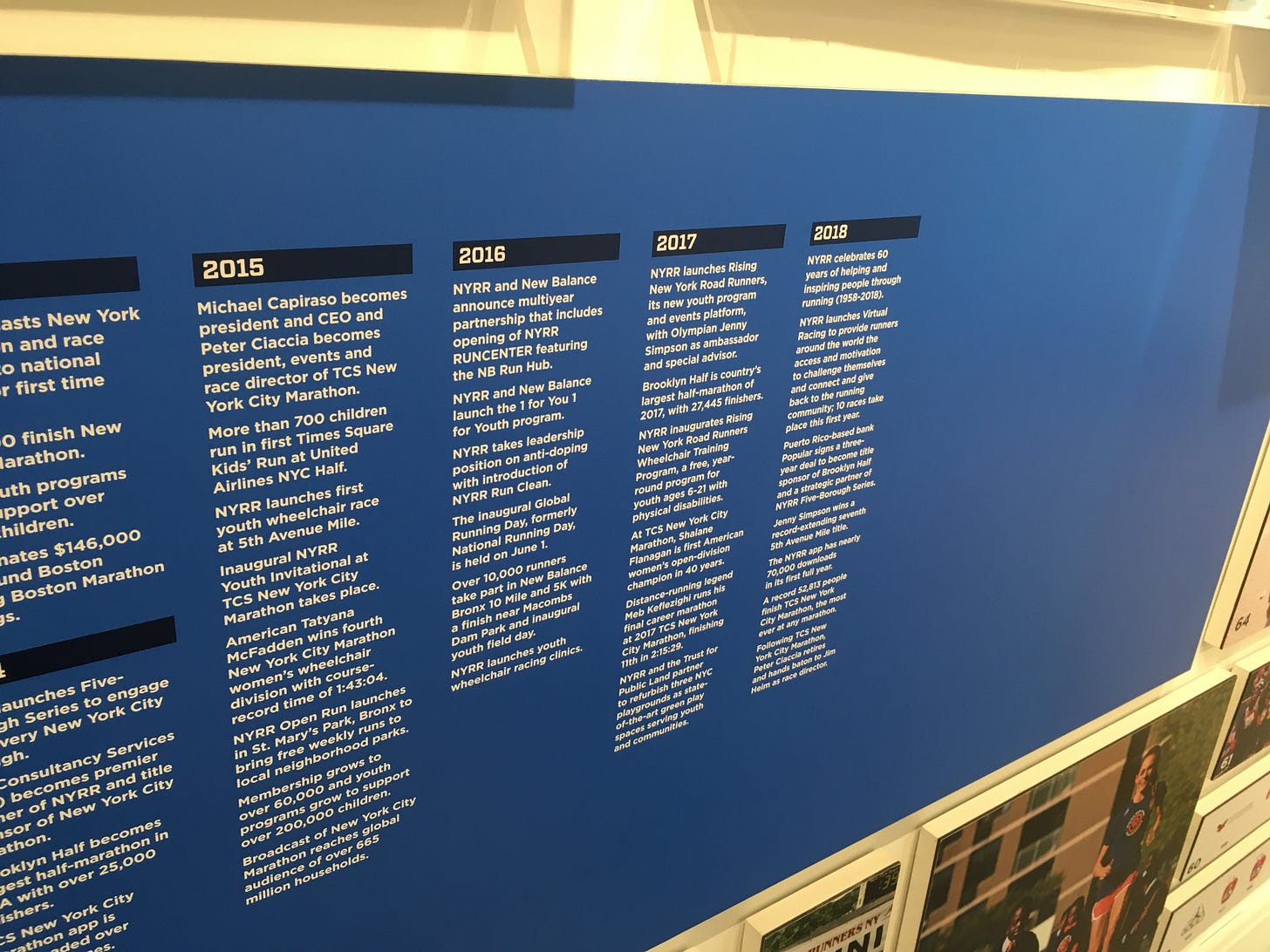

At our first meeting, he told me about NYRR’s RunCenter. He rates building and opening the RunCenter as one of his top accomplishments at NYRR, behind growing the youth running community in NYC and increasing the number of free-of-charge events and programs across the five boroughs.

“The RunCenter was the epitome of what I wanted the community running scene to be. I made everything I possibly could free there, so it would be a welcoming place for the running community.”

“It was a hub for me for five years. At least 5-6 days a week, and usually seven, I’d have a foot in there. At some point during the day, I’d hang out there with runners, hand out bibs, hand out t-shirts, or just be there to talk with runners and the team that supported the community. I would take meetings there and meet people there for runs. I loved it.”

Given all of that, the RunCenter was the focal point for some of his more intense exposure therapy.

“It sucks standing in front of it. The therapist wanted me to walk across the street and walk in front of it, which I think I did once. She wanted me to go in it and I refused. I still do to this day.”

Michael urged me to visit the RunCenter on my way to the airport. If I did, he asked me to see if his appointment as CEO in 2015 was still on the wall-length timeline of NYRR’s history. He vacillated over whether he wanted me to report back. An hour or so later, I let him know that NYRR had not fully erased him from their history.

To this day, “it’s still one of the most hurtful things that I can think about as far as a physical place. If I get within a two block radius, I feel the PTSD take over. Even on my last birthday, when we were getting pizza before going to a filming of The Daily Show, I had to make sure we didn’t walk down that block.”

Counter-narrative is always playing catch-up

Canceled people can’t pick up where they left off because their story ended the day the mob’s stories about them took over. They had the continuity of their life stolen from them, and somebody else spliced into their story a work of fiction or just random graffitti.

Because of his persistence, The New York Times, The Daily Beast, and a few other outlets have since modified their articles in some way to acknowledge the falsity of their initial claims and shallowness of their reporting. change.org took down the employees’ petition in 2022; and in November 2025, Meta removed a dozen of the posts from the anonymous Instagram account that personally disparaged Michael.

But all that does is dull the story going forward. “You spend years trying to undo something that you can’t undo. It’s never going to be gone. It’s never going to go away. You can only try to keep getting more of the truth out there so at some point people can read more of the counter-narrative than the original narrative.”

Only one major publication is still digging in their heels to stick to their original story: Runner’s World. Layering on the ironies, George Hirsch was the worldwide publisher of Runner’s World for 17 years; and the NYRR RunCenter is in a building owned by Runner’s World’s parent company, Hearst Communications.

People see what they want to believe

The downside of being able to pass as someone who’s back on track, all systems normal, is that it lets other people off the hook for the consequences of the cancelation. Anyone who might have carried a twinge of guilt over what they did to the target—or what they did not do for him—can exhale with relief: “See, it was an unfortunate chain of events, but things turned out OK.” For anyone else, the apparent normalcy keeps them ignorant of what cancelation actually is, what it does, and what it means.

Post-traumatic stress symptoms like triggers, flashbacks, avoidance behaviors, depression, and gaps in memory are common among canceled people. So are some of the consequences of PTSD, like drug and alcohol abuse, and suicidality. Interestingly, some of the more effective when-everything-else-has-failed treatments for “traditional” PTSD are similarly effective for canceled people.

Looking out the window of his apartment the week before the marathon, Michael sees the tell-tale sign of mass participation sporting events: crowd control measures and banks of port-a-johns.

“I’m probably about 200 yards from the finish line. They’re putting the police barricades on the street. The whole city is full of it. It’s a miserable few days. This was my favorite day of the year in New York City. Now it is my most difficult day of the year,” which is why he left the city for marathon weekend, as he’s done the last four years.

Not that he eagerly returns to the city for the rest of November. Given that his cancelation was sealed the week of Thanksgiving, his most difficult day of the year is a flackback-laden opener for his worst month of the year.

Related:

The former head of the New York marathon cleared himself in his sport. Now, he’s rebuilding (The Athletic)

A Rough Road Back (Road Race Management)

No ‘Morning After’ for Victims of Cancellation (Reality’s Last Stand)