Soccer blacklist exposed info about teens, pros, execs

Why were teenage girls and boys, two former CEOs, and two national team players on the same blacklist as convicted violent felons? And how was I able to see it?

The US Soccer Federation maintains a public list of individuals who are disqualified from participating in soccer. Most sports’ national governing bodies do the same. Some are ineligible only for one sport based on a determination by the federation. Others are banned from all activities in all sports via the US Center for SafeSport.

However, US Soccer also kept and circulated an unofficial, internal blacklist. This list contains 20 minors, two former CEOs of the US Soccer Federation, a Women’s World Cup winner, a US Men’s National Team player, a former commissioner of the National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL), and a former team owner in the NWSL. Four of the minors were added at age 10. They are all alongside convicted sex offenders, an undocumented immigrant accused of murder, over 200 people permanently banned from American sports, and nearly 3,000 others who have in some way run afoul of US Soccer or the US Center for SafeSport.

Due to careless controls, it was publicly accessible for at least several months, and possibly several years.

The list contains not only names but dates of birth and states of residence, making it a significant breach of data privacy in addition to the potential reputational, social, and professional harm.

Many of the individuals on this unofficial list have not been sanctioned by the Center. Their cases have not even been adjudicated: they remain in one of two “hold” statuses, some for over three years.

Privacy and due process in equal measure

Because holds are non-conclusive and do not entail any sanction, the Center’s decisions to place a case in a hold are rarely made public. Only the parties involved and the relevant federation(s) are informed.

Congress chartered the US Center for SafeSport as the national sport safe guarding organization in 2018, after the Larry Nassar abuse scandal at USA Gymnastics.

The Center has expansive latitude to write and enforce its policies. The Centralized Disciplinary Database is one of the few specific requirements Congress imposed on the Center: “publish and maintain a publicly accessible internet website that contains a comprehensive list of adults who are barred by the Center.” While the Center’s decision regarding a complaint is almost fatally public, how the Center reaches such decisions is opaque.

The Center imposes tight restrictions on the disclosure of its proceedings and decisions. The parties to a case are free “to discuss the incident, their participation in the Center’s process, or the outcome of that process.” However, neither they nor anyone else involved may release or share any of the Center’s work products, any evidence or transcripts from the proceedings, nor any statements from the proceedings “except as may be required by law or authorized by the Center.” Doing so is a sanctionable offense in itself.

The only permitted release is that the individual sport federations “may disclose the outcome of the matter...to those parties or organizations with a need to know” so that they can act in accordance with the decision.

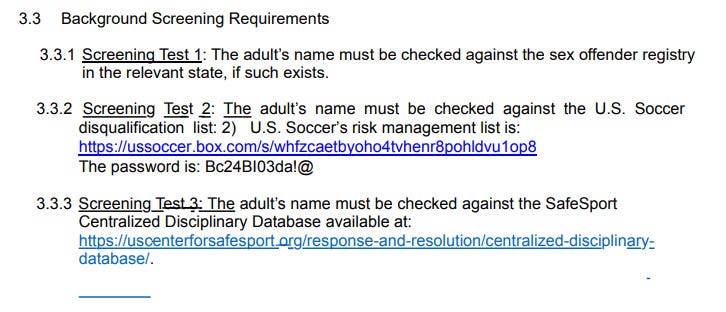

Upon compiling their disqualification list from the Center’s decisions and their internal processes, US Soccer made their list available to its member associations by providing a password to a shared folder on a commercial cloud storage service.

Several of those member associations published the link and password to the disqualification list on publicly available PDFs, making the list accessible to anyone online.

When someone brought this to US Soccer’s attention earlier this year, the federation responded by instructing that individual via his lawyer to destroy or delete the file, and to cease and desist from sharing it. He affirms that he has never shared the file. US Soccer subsequently changed the password to access the file in the cloud. At least one association, the US Adult Soccer Association, updated their publicly accessible PDF with the new password, keeping it available to anyone who came across that document.

At some point between May 2025 and the present, US Soccer changed the password again, and the list is no longer publicly accessible.

Several soccer associations included the unofficial list as part of a three-step process for background screening new adult volunteers, contractors, or employees; and all used the same verbiage to do so. Before bringing on someone new, these organizations were instructed to check the individual’s name against their state’s sex offender registry, the US Center for SafeSport’s Centralized Disciplinary Database, and this internal disqualification list.

That trio speaks to the destructive potential of being “listed” by a sports organization.

Sex offender registries present several constitutional problems, such as listing individuals for the remainder of their lives, even after they are released from prison. But being listed on a sex offender registry follows conviction and sentencing in a court of law, with all the due process protections those entail.

Individuals on the Center’s database or a federation’s list receive no such protections: no hearing before being listed, no adversarial process, no discovery, no neutral finder of fact, no neutral arbiter. But they still end up sex-offender-adjacent on these lists and in the minds and conversations of people within their sport: people who may be evaluating them for jobs or, in the case of the minors, recruiting them for collegiate athletics, which can spill over into college admissions.

Protecting who from what?

The presence of violent felons and infamous pedophiles on these lists forces the question: how do three 10-year old girls and some teenage boys and girls end up there? And with the Center repeatedly lamenting their case backlog and insufficient funding in front of Congress, are these kids the best use of the Center’s resources?

Soccer moms and dads will usually talk your ear off about anything involving their child and the beautiful game. Unsurprisingly, this topic is an exception. None of the few parents or coaches who responded to me were willing to speak on the record. Some mentioned the anxiety that hit them upon receiving my messages, thinking and hoping that this was hidden in the past.

But these matters are not in the past for many of them because of the nature of a SafeSport “hold.”

A case is placed on an “administrative hold” when “there is currently insufficient information to proceed with an investigation.” The Center “may re-open [the case] at any time when sufficient information is made available.”

A “jurisdictional hold” means the Center does not have jurisdiction over the accused party, typically because the individual is not a member of a sport federation. In these situations, the Center plays the long game: if “the individual becomes or seeks to become a Participant in [a national governing body’s sport], the matter will undergo the Center’s investigative process.”

There is no time bar or statute of limitations for enforcement of the SafeSport Code, so either hold is a lifetime shadow ban from sport.

Some of the other minors on the list were suspended or placed on probation for a set number of months. However, even after that time elapsed, they remain on US Soccer’s internal blacklist, extending the practical duration of their punishment. Several others are serving “temporary suspensions.” But given that over a dozen individuals on the Centralized Disciplinary Database have been “temporarily” suspended for up to six years, these young players have an uncertain future in and out of sport.

Perhaps they can get some help from the American soccer luminaries similarly tarred.

Related:

The Sex Offender Registry: Vengeful, unconstitutional and due for full repeal (The Hill)

Temporary punishments permanently damage athletes’ careers (Abuse of Process)

Congress’s Sex Abuse Enforcement Body Nailed For Fraud, Pattern Of Misconduct (The Federalist)

The Evolution of Unconstitutionality in Sex Offender Registration Laws (Hastings Law Journal)

This was a tough read personally experiencing Safe Sports clear agenda to protect their chosen ones. Chris Gutowsky, who owned Cynisca cycling team, was sanctioned for harassment of myself. Never published or made public. He also has several complaints of verbal abuse by his athletes. Again, nothing ever made available.

Thank you, George, for another powerful post.